I-Team: Thousands Of Runaway Incidents Of Kids In DCF Custody

BOSTON (CBS) - Kids in state custody ran away more than 3,400 times over a three-year period, according to figures the WBZ I-Team obtained.

Some of those children ran away repeatedly, while 30 of the kids were missing for a year or longer, the records show.

The WBZ I-Team received the data from the Department of Children and Families (DCF) 10 months after making a public records request in January for all runaway incidents from 2013 to 2015. Along with the date the child went missing, the records also show how long children were gone before being returned to their DCF foster home or other residential placement.

The I-Team has also learned DCF just implemented its first policy devoted to children on the run. The set of guidelines spells out when to contact police, launch search efforts, and identify kids who are at a high risk to run.

'I've lost count' how many times son has run away

In 2014, Kristi Emanuel moved to Boston with her two sons to escape a life of domestic violence. After bouncing from shelter to shelter, Emanuel said DCF intervened and took custody of her kids.

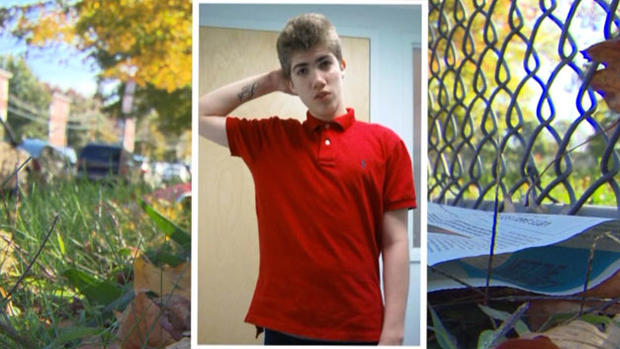

Almost immediately, her oldest son, Ben, started running from his DCF residential placement at a group home.

Sometimes he showed up at Emanuel's domestic violence shelter. But the 16-year-old has also made it all the way to Florida twice.

"I've lost count of how many times he's run away," Emanuel said. "That was one of the reasons DCF took my children. They said I had lost control. But since Ben has been in DCF custody, they haven't done any better."

Emanuel contacted the I-Team after a stolen vehicle flipped in a Roxbury neighborhood right in the middle of the school day in September. Three juveniles inside the SUV were rushed to the hospital.

One of those teens was a friend of Ben's from the DCF group home. Emanuel said several frantic hours passed before she learned Ben wasn't also in the vehicle.

"I didn't know if my son was dead or alive," she said.

Emanuel later learned Ben had been asked to drive the stolen SUV that day, but had declined. As the mother works toward reunification, she hopes her son is placed in a living environment that keeps him from running away again.

"I just feel like there has to be some kind of accountability," Emanuel said. "This has been more traumatizing than the domestic violence."

On average, kids gone more than a month

According to the runaway statistics, kids were gone an average of 36 days. But some were missing a lot longer: 140 teens were on the run for the length of an entire 180-day school year. The longest time period on the list was 711 days.

Besides being located and returned to DCF custody, teens also moved off the list when they turned 18 years old. It was unclear how many kids on the list became adults while they were still on the run.

Some kids ran away repeatedly for short periods of time. For instance, one child had 21 incidents for a total of 79 days.

But there were also troubling examples like this: a teen who ran away five different times and was missing for a total of 1,080 days.

Mary McGeown, the executive director of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, would like to see those numbers change.

"This is a really important issue," she said. "My question is, what are we doing to keep those kids from becoming missing or absent from a program? Or if they are missing, how do we locate them and get them back as quickly as possible?"

The WBZ I-Team requested an interview with DCF Commissioner Linda Spears to get insight on the runaway statistics, but the agency declined.

"I think DCF should be willing to share info and answer questions," McGeown said. "These are our children."

New policy on finding, preventing runaways

Maria Mossaides, Child Advocate for the Commonwealth, said it is difficult to analyze the runaway statistics without digging into individual case files.

However, with an increasing number of kids in DCF custody (about 9,500) because of the opioid epidemic, Mossaides said the policy is overdue.

Both McGeown and Mossaides applauded the development, the latest reform for an agency that has been at the center of several high-profile tragedies involving children.

The child safety advocates would like to see DCF publicly post the numbers so the public can see DCF performance.

"Now the important thing is monitoring the policy for quality assurance to see if outcomes are improving, kids are being located faster, and incidents are being prevented," Mossaides said.

DCF spokeswoman Andrea Grossman said the new policy clarifies expectations for when to contact police, when contracted residential program providers should notify DCF, and when information should be shared with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

"The new policy is designed to strengthen placements and reduce the risk factors that cause kids to leave," Grossman wrote. "It provides additional guidance to social workers about ways they can talk to youth about why they leave placements in an effort to better identify services and treatment in an effort to prevent future runs."

As of November 14, Grossman said 81 kids in DCF custody were on the run.

Ryan Kath can be reached at rkath@cbs.com. You can follow him on Twitter or connect on Facebook.