Exponent Boasts About Correct DeflateGate Conclusions In Bizarre New York Times Feature Story

By Michael Hurley, CBS Boston

BOSTON (CBS) -- The only scientists in the world who believed the Patriots' footballs were unnaturally deflated by a person are the same people who are the only scientists who were paid handsomely by the NFL to investigate that conclusion.

And yet, despite dozens of scientists around the country putting in extensive work to prove them wrong, the folks at Exponent are spiking the football.

"Now that Brady has accepted his punishment and is sitting out," John Branch wrote, "Exponent is finally talking. And it wants everyone to know: It was right all along."

Strangely, The New York Times was more than happy to give Exponent a blank slate to create whichever record the company wanted, releasing a 5,000-word feature story that was heavy on the claims of Exponent and light on anything else.

As a refresher, the NFL simply could not afford to be proven wrong in "DeflateGate." By the time the "investigation" was launched, the league had already lost control of the story. With several of his own employees tangled up in misbehavior in the process, commissioner Roger Goodell had to restore order.

Coincidentally, the NFL could afford to ensure that it would not be proven wrong. Enter Ted Wells, and enter Exponent.

The rest is, of course, history, but Wednesday's Times story has brought Exponent back to the forefront in a story that reads more like a press kit than it does a bit of journalism.

To wit: the story makes several references to other scientists and physics professors who argued against Exponent's findings. Yet the story references zero of the specific claims made by these scientists, and it includes zero explanation from Exponent on the specific criticisms.

While the average reader may not be capable of digesting something like Drew Fustin's "The Physics Of DeflateGate" or MIT professor John Leonard's 15-minute debunking of DeflateGate (which was covered by the NYT), the average reader certainly can understand the idea of doctored images used to try to massage a point that shouldn't be massaged.

For example:

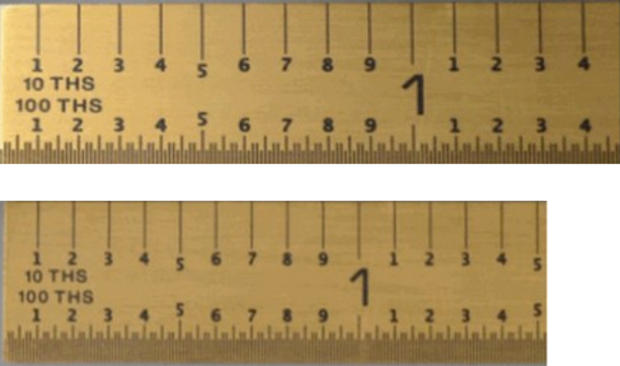

That photo comes from Exponent's portion of the Wells report. For one, in an attempt to make the needles appear to be closer in size to each other (thus making the manufactured narrative of Walt Anderson "possibly forgetting" which needle he used to measure the footballs), the needles are measured from different locations. One is measured from the start of the ruler, while the other is not measured from the same starting point. Additionally, as first noted by Robert Blecker, the sizes of the images have been manipulated. Here is the ruler from the top image and the ruler from the bottom image, isolated but not manipulated in any way by me.

This reputable scientific firm made an honest mistake by committing an error that would have earned a high school junior an automatic "F" in physics class? Or Exponent is exactly what its critics make it out to be?

The choice is up to you.

Here are some of the highlights from the NYT feature:

--"Everyone was an expert, it seemed, willing to explain why the game balls used exclusively by the Patriots were so far below 12.5 pounds per square inch, the N.F.L.'s lowest allowable limit, and whether that even mattered."

That's a factual inaccuracy. Based on basic science, 21 professors from around the country determined that depending on pregame inflation levels, anywhere between 38 percent to 82 percent of all NFL games were played with footballs with a PSI measurement below 12.5. The "NFL's lowest allowable limit" is a myth.

--Here's a quote from Exponent's Robert Caligiuri. It's best if you read it in Donald Trump's voice. Seriously, try it out:

"We knew there would be controversy here. And we needed absolutely the best people we could possibly put on it. That's why I organized it the way I did. I knew the way to approach this — and frankly we had seen the news, we saw the people blaming it on the way he rubbed the footballs and people talking about it and stuff — and we knew that there were some questionable things out there already. So we knew we needed to be totally bulletproof here."

Frankly, folks, we needed the best. The best scientists. And I got them.

OK, Rob. Facts say otherwise.

--Here's a quote from John Pye, the chief researcher into the footballs.

"The visibility of this project fits into some of the largest that we do at this firm. But when you think about the impact? Meh. Not so much. No one is losing their lives here. The building is not burning down. The vehicle is not crashing. The product is still working. Nothing's caught on fire."

Meh. Really not that important. Meh.

That quote was followed with the obvious question from the writer: Why get involved if it's not important at all?

Caligiuri said something about solving an interesting scientific case. But there's a growing suspicion among the sentient community that Exponent's involvement had more to do with the profits associated with such high-profile "research."

--Pye dazzled and wowed the writer by squeezing a football and guessing that its PSI was 12.3. It was 12.25. That's close! And at Exponent, being "close" is really all it takes.

Also, even if Pye possessed a strange sixth sense and could be a human pressure gauge ... that wouldn't dispel the scientific arguments made by dozens of brilliant people from all over the country. But hey, it makes for a nice anecdote.

--"As part of those experiments, Pye set up a television replaying the game in real time. Exponent employees imitated what they watched — throwing the balls, falling on them, shuffling them out of play, wiping them with towels, spraying them with water to simulate rain."

A bunch of scientists jumping all over footballs in a climate-controlled chamber. Is there video of this? Please let there be video of this.

--The New York Times did not deem it fit to print that Exponent has concluded that secondhand smoke doesn't lead to lung cancer. Kind of an odd omission. Likewise, The New York Times didn't mention Exponent's conclusion that "dumping oil waste in the Ecuadorean rain forest did not increase cancer rates." Instead, the story chose to list a number of "critics" of Exponent and then write them off for various reasons. This was, in all seriousness, a very odd thing. Instead of questioning Exponent on specifics, the story served only as a microphone to Exponent to say whatever it wanted. This is most curious.

--UPDATE: After the story went live, some tweets from the story's writer came to light. They help explain why he didn't provide the type of pushback on Exponent's claims that some basic interrogation would warrant.

Much like Exponent, it appears as though Branch operated under the assumption of guilt from the start. Did it color his reporting? That's up to the reader.

--Fortunately, Pye was kind enough to speak down to you, the normal person, the non-scientist, in a way that allows you to better understand this world.

"The real world is the real world — it's not a binary thing. Binary is a human invention; the real world has a continuum. So you need to understand where your work fits on that continuum."

Thank you, oh wise sage. I now understand this world in a non-binary fashion. Thank you for this.

(Also, science and math are both black and white.)

--Among the biggest failures by the non-scientists who conducted the halftime measurements was the failure to record the times that the measurements were taken. This was a critical argument, one that forced Exponent to work backwards based on the NFL's assumption, rather than work based on accurate scientific data. This was a massive, massive hole in Exponent's report.

The NYT story briefly addressed the problem that this presented ... and then moved on.

No explanation. No anything. Just this next bit.

--"In the end, Exponent said that it could not 'determine with absolute certainty' whether there had been tampering with New England's balls. The insinuation was more damning."

The insinuation. Guilty by insinuation. Four games. First-round draft pick. Based on the insinuation of a company that's supposedly dedicated to science.

--Caligiuri staunchly defended the research. He sharply criticized the scientific community for raising valid concerns with his report when he said:

"If you're going to look at what someone else has put forward as a hypothesis, a theory or experimental verification, you have to understand what they did, and then work from there. And I'm not sure that everybody did that."

Au contraire mon frère. I think that's exactly what everybody did.

You can email Michael Hurley or find him on Twitter @michaelFhurley.