Socci's Notebook: Education From A Coach Continues With Belichick's Advanced Football History Lesson

FOXBORO (CBS) -- I was eight games into my first full season as a football announcer when an old coach pulled me aside for a history lesson.

He'd heard something I said a few days earlier and wanted to set me straight. My comment in question, uttered on a Navy broadcast, referenced the background and philosophy of then-Rutgers head coach Terry Shea.

Shea had been an assistant to Bill Walsh at Stanford, coaching the same West Coast offensive scheme he was trying to transplant on the East Coast as his Scarlet Knights visited Annapolis in the fall of 1998. Speaking in -- and of -- passing, I mentioned the ties between the two, before repeating a conventional characterization.

"The father of the West Coast offense," I called Walsh, giving him sole credit for the system most closely associated with his great 49er teams of the 1980s. There was nary a mention of anyone else.

Steve Belichick was listening. And when he spotted me on the Naval Academy yard the following week, he kindly offered an education on the evolution of an offense. His discourse began and ended with Paul Brown and Sid Gillman.

Long before being tagged with its moniker -- by Bernie Kosar of all people -- which occurred well after it was first installed by Walsh -- in Cincinnati of all places -- the West Coast model was inspired by other great football thinkers. Even the late Al Davis, a devotee of the long ball, occupies a spot along the timeline. Walsh went to work under Davis, after the latter worked under Gillman.

That experience taught me a few things. Nothing in the game is thought of out of thin air, specifically the short-passing game suited to an ex-Bengals quarterback named Virgil Carter and perfected by an all-timer known as Joe Cool (Montana). Not to mention, the more some of us learn about football, the more we realize how little we know.

That is why crossing paths with the senior Belichick, a regular inside the Academy's Ricketts Hall as a retired Navy coach and phys ed instructor, was always so enlightening for so many who worked around the Midshipmen. In those moments you were privy to a professor of the sport.

Steve Belichick died at 86 in November 2005, hours after watching his beloved Navy defeat Temple and on the eve of another win for his son Bill's New England Patriots team over New Orleans.

My play-by-play calling is no longer devoted to the college patriots of Annapolis but rather the NFL's Patriots of Foxboro. Still, all these years later, I occasionally get to experience an advanced course about the game from a coach named Belichick.

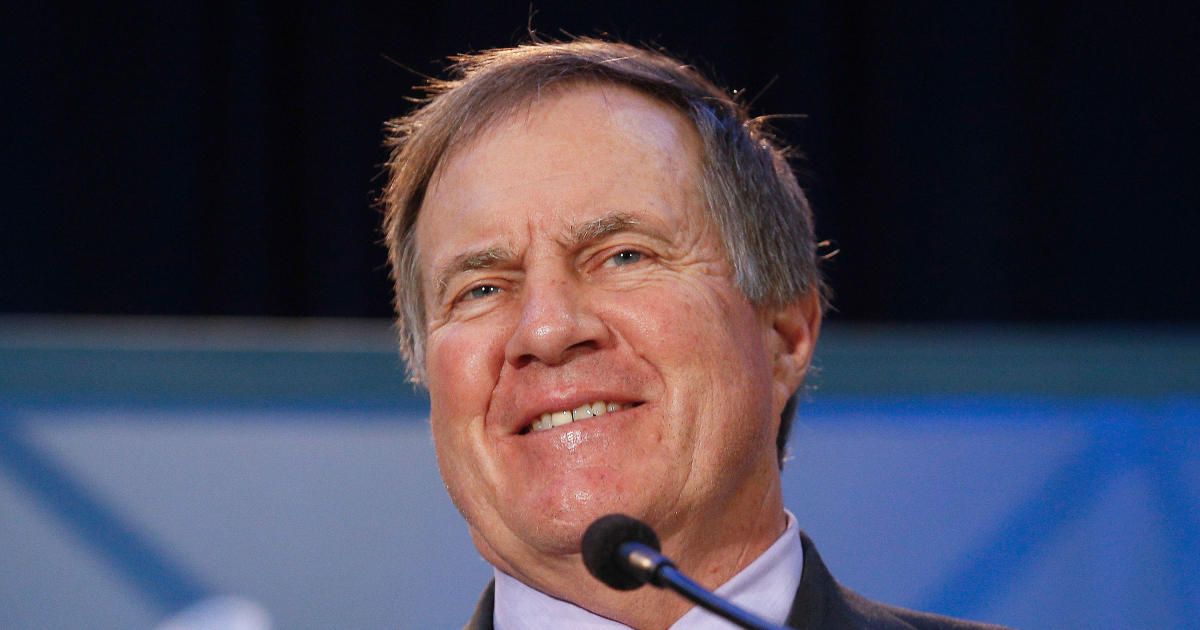

Wednesday was one of those days. Late in his mid-week press conference, Belichick was asked to contrast what the Pats did Sunday in Minneapolis with what the Colts did Monday in Indianapolis.

One team utilized an offensive tackle as a tight end in its victory over the Vikings. The other employed an unbalanced line in a loss to the Eagles. It shifted a tackle from one end of the formation to the other and filled his vacated spot with a tight end.

"It's a lineman instead of a tight end, but if it was a blocking tight end or lineman, how much difference is there? I'd say there's a smaller degree of grade of adjustment for the defense," Belichick said of the Patriot way last weekend, before addressing the Colts' tactic. "Once you flip a lineman over, now you've totally changed the defensive spacing.

"What was a three-man surface is now a four-man surface. What was a three-man surface is now a two-man surface. That creates some fundamental blocking angles potentially for the offense. I'd say that there's a lot more involved in that."

Such as, Belichick pointed out, blocking assignments associated with pass protections.

"I'd say normally you'd have to simplify your protections quite a bit rather than try to run them all from an unbalanced line," he explained. "I'm not saying you couldn't do it, but it would take a lot of work, I would think."

Belichick also viewed it from a defensive perspective. He discussed the ways defenses can adjust to the unbalanced look, which tends to tilt an offense's "passing strength," as Belichick termed it. And he got into possible limitations for the ground game.

"Some of your weak-side runs that you were running behind a tackle, now you're running behind a tight end," he said. "So you have to know where the defense is going to be when you call some of those plays, which gets again, a little bit more involved."

With that, the discussion itself became even more involved.

"I think it's hard to be in an unbalanced line and just run one or two plays because you don't know if the defense is going to move over or not move over, rotate away from the formation passing strength, rotate to it," Belichick continued. "But, if you have a number of plays then no matter what (defenses) do, then theoretically, just like everything else in your offense, you can (determine), 'If they do this, we do that. If they do that, we do this.'"

Soon the coach's speak transitioned from X's and O's to a trip down memory lane, intertwining football history with Belichick's personal past. He noted the offenses of the 1930s and '40s, recalling the single-wing; both balanced and unbalanced.

"In a way I really feel lucky because the one year, in eighth grade I played for the T-Birds in Annapolis," a smiling Belichick recounted of his experience in the early '60s as a 110-pounder on a team sponsored by a Ford dealership. "Our coach played college football at Clemson so we ran the single-wing."

From there, Belichick moved on to high school at Phillips Andover, where he played in the wing-T, and college at Wesleyan, where he blocked in the wishbone. And then as a coach, there was in his words, "all the NFL stuff since '75."

Along this sentimental journey, Belichick stepped back to revisit a crossroads the game encountered more than a half-century ago, when offenses graduated from the single-wing to wing-T. How they utilized certain players led to success for many of the NFL's greatest stars.

"All those single-wing teams in the '50s had to make a decision when they went to the T-formation (with) what they were going to do with the tailback," he said. "When all those guys came into the NFL, (there) was the decision the NFL had to make with them. Paul Hornung, you put him at running back. Johnny Unitas, you put him at quarterback. Bill Wade, you put him at quarterback.

"You had single-wing tailbacks that ended up becoming halfbacks in the NFL or they became quarterbacks in the NFL because that was their combination job in the single-wing offense. Of course, nothing was more important than punting (for) the great single-wing tailbacks like Sammy Baugh. Punting was really such a big part of it then that your single-wing tailback had to be a good punter."

Perhaps his rich appreciation of such history is another reason why Belichick values his own quarterbacks so highly.

We've all seen Tom Brady pooch punt, as he did most famously in the snow 11 years ago against Miami and more recently last December vs. Buffalo. Meanwhile, Jimmy Garoppolo punted nine times in his Eastern Illinois career, averaging 31.9 yards per kick.

Then, as far as we know, neither ever kicked from the single-wing.

In all, Belichick's oral dissertation lasted close to 10 minutes in a near half-hour session otherwise devoted to Sunday's meeting of the Patriots and Oakland Raiders.

Even for those of us who are hardly football wonks -- please don't ask me to quickly differentiate a 'three' from 'five' technique -- the education from a coach was a fascinating exception to what is usually excerpted from press conferences.

SPEAKING OF THE RAIDERS

Belichick opened Wednesday's presser by sharing a general impression of a Raiders team loaded with newcomers who are old by NFL standards.

They include defensive ends ex-Giant Justin Tuck and former Steeler Lamar Woodley. Joining the likes of 17th-year safety and 37-year-old Charles Woodson, they were lured to Oakland in a free-agent spending spree by third-year general manager Reggie McKenzie.

"It's a lot of familiar faces, but guys who we've been used to seeing in different uniforms," Belichick said. "I think the thing that jumps out about the Raiders is how experienced they are, how many veteran players they have. "

Belichick added that the Raiders strike him as big and fast.

Indeed, Oakland has some explosiveness. One example is linebacker/defensive end Khalil Mack, the fifth overall pick in this year's draft. Belichick referred to him as "a force out there."

Nonetheless, as the winless Raiders (0-2) come to Foxboro seeking to end a 14-game losing skid in the Eastern time zone, they're making their second cross-country trip in three weeks. They opened with a 1 p.m. kickoff at the New York Jets.

During the CBS telecast of that 19-14 loss in the Meadowlands, where the Jets opened with a somewhat hurried offensive pace, analyst Phil Simms relayed an exchange he had with New York quarterback Geno Smith.

"'Why do you want the up-tempo offense?' I asked him," said Simms. "He goes, 'Man, they got a lot of a lot of old guys over there and we want to take their legs away from em.'"

It stands to reason the Patriots may very well look to play the same way, if not faster at times, against an aging and presumably jet-lagged Raiders defense.

Just don't expect them to do it out of an unbalanced formation.

Bob Socci is the radio play-by-play voice of the New England Patriots. You can follow him on Twitter @BobSocci.

MORE PATRIOTS COVERAGE FROM CBS BOSTON